On 16 May, the MA students were honoured to attend a full day masterclass with Terese Svoboda, the author of six novels, a short fiction collection due out next year, seven poetry collections, a book of translation, a biography and a memoir. Her novel Cannibal was named one of ten best westerns of the year and described by one reviewer as ‘a female Heart of Darkness’. Her video work is also award-winning and she’s received a Guggenheim.

On 16 May, the MA students were honoured to attend a full day masterclass with Terese Svoboda, the author of six novels, a short fiction collection due out next year, seven poetry collections, a book of translation, a biography and a memoir. Her novel Cannibal was named one of ten best westerns of the year and described by one reviewer as ‘a female Heart of Darkness’. Her video work is also award-winning and she’s received a Guggenheim.

Our day consisted of readings, conversations about Svoboda’s work, discussion of others’ work and an in-class exercise. During the first session of the day, Chris Price introduced Terese to us. What followed was a lively conversation full of insight and refreshing (sometimes daunting) writing advice. Below are a few of many highlights.

Mother burns the bridge

Terese reads us ‘Bridge, Mother’, a poem powerful in its sparseness. Simple words (‘mother’, ‘burns’, ‘bridge’, ‘other side’, pronouns, articles and the like) are arranged in declarative sentences to produce different, sometimes contradictory emphasis or information. This stark unemotional language produces a startling emotional effect.

How to achieve this powerful simplicity? Terese tells us she had twenty constraints in this exercise – it’s an exercise Chris knows, it turns out, so she can share it with us. And it took a mere ten years to write. So get to work everybody!

Cannibal

Terese began her writing life as a poet, but an experience in her young adult life with a social anthropologist filmmaker boyfriend in Sudan  made her want to write fiction. This became Cannibal, her first novel. It was fifteen years in the making, during which time she grappled with some of the differences between poetry and fiction. Poetry occurs in a single moment on a white page, whereas fiction, she was told, emphasised character development and plot, and she was always bored with how to open and close doors in the prose. She says if she weren’t always ‘rebelling against these things’, she would have learned earlier that ‘story is a magical thing that you unearth and discover’ – but magic takes work.

made her want to write fiction. This became Cannibal, her first novel. It was fifteen years in the making, during which time she grappled with some of the differences between poetry and fiction. Poetry occurs in a single moment on a white page, whereas fiction, she was told, emphasised character development and plot, and she was always bored with how to open and close doors in the prose. She says if she weren’t always ‘rebelling against these things’, she would have learned earlier that ‘story is a magical thing that you unearth and discover’ – but magic takes work.

Gordon Lish

A turning point in Terese’s writing life was attending Gordon Lish’s famed writing workshops. She describes these in riveting detail. Lish looked ‘like a Presbyterian minister’, she says, ‘but kind of evil, like Sam Peckinpah’. You weren’t allowed to pee at any point during the sessions, even Terese, who was pregnant at the time. Not only that but the sessions were very long: it wasn’t unusual to finish up at 2am. People would break down, there would be people next to her on respirators, people with two weeks left to live. He made you believe fiction was worth devoting your life to. It was like EST or brainwashing, you emerged believing that.

A turning point in Terese’s writing life was attending Gordon Lish’s famed writing workshops. She describes these in riveting detail. Lish looked ‘like a Presbyterian minister’, she says, ‘but kind of evil, like Sam Peckinpah’. You weren’t allowed to pee at any point during the sessions, even Terese, who was pregnant at the time. Not only that but the sessions were very long: it wasn’t unusual to finish up at 2am. People would break down, there would be people next to her on respirators, people with two weeks left to live. He made you believe fiction was worth devoting your life to. It was like EST or brainwashing, you emerged believing that.

It wasn’t all mind control though. Lish was welcoming to poets. He liked the ‘torque’ that words by themselves could lead you to, he encouraged people to stop and see how a text could unfold, one word at a time, as if he were ‘pulling a pearl necklace out of his mouth’. He didn’t believe in conventional plot. The only challenge for him was to get the reader to turn the page. Plot for Lish was like the Native American practice of shooting an arrow toward the sun, going to pick it up and then shooting again. A feeling of not knowing where you’re going was important to him. Because of this, he encouraged the use of first person, present tense. It allows things to unfold for the writer at the same time as the reader.

These lessons were liberating for Svoboda. ‘Fuck it, I didn’t have to do anything the way I was supposed to.’ She discovered what she needed to do with her novel: start again and proceed word by word. She never looked at any of the previous versions. ‘I thought nobody would ever publish it and that was a relief.’ (Of course it turns out she was wrong on that count.)

The Ps of writing

Play is what you’re in it for, not just for the dopamine rush when you’re really ‘in it’, Terese says. Her novel Pirate Talk and Marmalade was developed out of the considerable constraint that the entire thing would consist of nothing but dialogue between two or three people. ‘I was told I was very good at description so I decided to do this book without any description,’ she says. ‘Just say no to me and I’ll do fine.’

In light of this, Chris suggests that perversity is another writing tool. ‘Perversity and perseverance – the two big Ps, yeah,’ says Terese. If you get stuck, turn to another form. The constraints of one form can enliven another. It also helps to leave things for a while. ‘I’ve got drawers,’ she says.

On anger

Revenge can be an important motivator for your first book, Terese tells us. Anger is what helps get you through all that learning. But it’s hard in that mode to make the character you’re trying to describe sympathetic – so that’s especially where the fiction comes in.

One helper in this regard is the compression of memory. Detachment helps too. This is why hardly anyone writes a good deathbed book. Everyone starts with their traumatised childhood because everyone has one.

Anger is also often the driving force behind political poetry. A political poem is harder to write than a love poem, she says, ‘and that’s pretty darn hard to write’. ‘Let anything that burns you come out’, she quotes Lola Ridge as saying, and tempers this exhortation with a warning: find something to support your position with regard to anger, be sure to contextualize it. Speaking out with anger is seldom considered acceptable. An Adrienne Rich obituary described her as a ‘poet beyond rage’, not an angry poet. The New Critics hated women and regarded them as ‘shrill’ rather than angry. A contemporary example is Hillary Clinton. Terese’s suggestion is to ‘flex the muscle of anger, don’t KO the reader’. But you have a responsibility to express anger. Poets are the only holders of truth. ‘I don’t wanna remain silent,’ she says. ‘Do you have a problem with that?’

Lola Ridge, ‘bad girl’

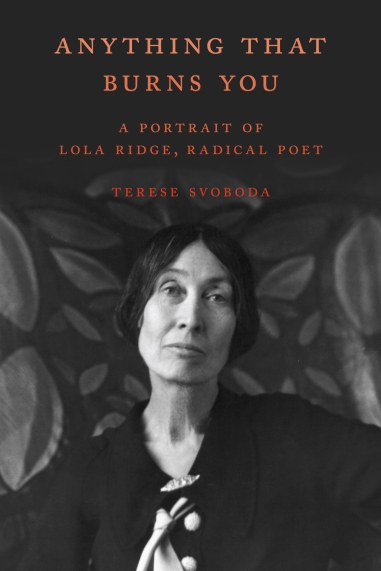

Terese wrote a biography of Lola Ridge, an anarchist Modernist poet and committed activist. Her second book was from the point of view of a little Australiasian bad girl. She was born in Dublin and emigrated to New Zealand as a child and spent 23 years here before emigrating to New York City, where she received very favourable critical attention as a writer and was an editor at avant garde literary journals. She had a personal relationship with all the big names in New York at that time (between the wars): Marianne Moore was one of her best friends. At her death, the New York Times declared her “one of America’s most important poets.” Despite this, she’s been largely forgotten in New Zealand and the United States. Why is that? Part of it has to do with the politics of the canonisers, Terese argues. Influential Elliot and Pound were elitist, whereas Ridge was vocally and uncompromisingly for the radical left. Women poets were also perceived as a threat during the time Ridge was active, following the immense publishing success of Edna St Vincent Millay. As a result, women poets were widely denigrated. She was also experimental at a time when poets looked for form. Others have seen her perspective with regard to her radical interests in those who were lynching or executed as ‘maternal’, but Terese argues that Ridge always writes from a female point of view and that’s so rare it’s seen as maternal.

Terese wrote a biography of Lola Ridge, an anarchist Modernist poet and committed activist. Her second book was from the point of view of a little Australiasian bad girl. She was born in Dublin and emigrated to New Zealand as a child and spent 23 years here before emigrating to New York City, where she received very favourable critical attention as a writer and was an editor at avant garde literary journals. She had a personal relationship with all the big names in New York at that time (between the wars): Marianne Moore was one of her best friends. At her death, the New York Times declared her “one of America’s most important poets.” Despite this, she’s been largely forgotten in New Zealand and the United States. Why is that? Part of it has to do with the politics of the canonisers, Terese argues. Influential Elliot and Pound were elitist, whereas Ridge was vocally and uncompromisingly for the radical left. Women poets were also perceived as a threat during the time Ridge was active, following the immense publishing success of Edna St Vincent Millay. As a result, women poets were widely denigrated. She was also experimental at a time when poets looked for form. Others have seen her perspective with regard to her radical interests in those who were lynching or executed as ‘maternal’, but Terese argues that Ridge always writes from a female point of view and that’s so rare it’s seen as maternal.

Ridge wrote one of her books on a drug called Gynergen, an amphetamine. This was a time in the United States, she reminds us, when no one drank (or at least, not legally) because of prohibition, but drugs were freely available everywhere. (And when Terese says everywhere, she really means everywhere. 7UP had Lithium in it until the 1950s!)

Ridge was also very ill with anorexia, only 69 pounds (31kg) at one point. She was hospitalized and sometimes bedridden as a result, which Terese thinks was not entirely a bad thing for Ridge’s work, as it gave her more uninterrupted time to write, and made her seem like a woman of leisure, more similar to her patrons’ lifestyles.

‘I’ll never write another biography’

‘I’ll never write another biography,’ Terese says. ‘It’s the drowning in the middle of a sea of facts.’ Some of the challenges of writing Lola Ridge’s biography in particular were: getting threatened with legal action for plagiarism; not having access to all the papers; and not knowing much about modernism (and the balance of making what she did learn about it accessible while also to making it readable for people who already knew about it), and having to craft information in a certain order so that the reader will already know one fact in order to understand another. The most Oulippian thing you can do is write a biography, having to stick with the facts, and support each sentence with a citation, she says. In the end, she couldn’t wait for Lola Ridge to die. The death scene, however, was miserable, but mitigated by the fact that her husband brought her breakfast in bed a few days earlier, a luxury she craved. Ridge had found strength in isolation, despite the sad circumstances of her demise. ‘I am my own citadel,’ she quotes Ridge as saying.

Writing Black Glasses Like Clark Kent, her uncle’s story of being a GI in post-war Japan presented different challenges. It’s both a personal story and a family story, and secrets surfaced that some of her family were unhappy about her sharing. However, she cautions us against worrying too much about family when writing from life, because you don’t always know what relatives will be offended by. She wrote terrible things about her mother in her first book, Terese says, and the only thing that offended her mother was a depiction of her wearing an ill–fitting sweater.

Svoboda was also uncovering secrets the US military didn’t want people to know when she was working on Black Glasses Like Clark Kent, about executions by the US military of their own soldiers. Getting information was hard. A mysterious fire at a remote archive in 1973 was often blamed for the inability to produce records. Terese says a librarian friend of hers recommends her book to anyone who’s doing research, because it keeps meeting dead ends and she had to find new leads. Writing a biography became similarly obsessive. You see your subject everywhere you go. It’s also expensive, because you have to travel to places physically in service of the obsession. She says that the trick with this memoir was to find a mystery that would lead the reader deep into the book.

The exercise

Our in-class writing exercise was as follows:

Select one word that has significance to you. Produce a lyric essay in five parts. Parts 1, 3, and 5 are personal memories in present tense, not necessarily chronological. Parts 2 and 4 are intellectual, analytical. They could involve quotes, myth, words used in literature or film, word derivatives, and so on.

We had a half an hour to write something based on this prompt, with access to an internet-bearing device for research if we needed it. We were to write for ourselves (it wasn’t collaborative).

Afterwards, Terese went around the room picking out people to read what they had written. Word choices were as diverse as ‘ontology’, ‘homeless’, ‘night sweats’, ‘yellow’, ‘doubt’ and ‘daughter’, and the resulting essays were as interesting and varied. In the end it turned out nobody was exempt from reading their essay aloud, including Emily and Chris. Perhaps had she warned us of this beforehand we might have made more cautious, self-censoring choices. After each reading, Terese provided an instant commentary on the work and often some more general writing advice, for example, ‘a way to get energy into a prose piece is to contradict yourself’. She also spoke about complexity in a character. We all contain the elements of a Dostoevsky character, a murderer or great lover, because we are all human. For a character to be believable, we need to know how they are like us.

Terese produced some more Gordon Lish nuggets in the course of this session. Lish made people confess to the worst things they’d ever done in their lives, she revealed. Somebody would break down making these confessions, and then he’d say ‘you didn’t have to tell the truth’. A work ‘has to make us cry, not you’. We’re to look for what makes us human, what moves us, for guidance. Fiction, according to Lish, is a sacred torch that’s been handed to us by someone else.