Cultural historian and writer Maria Tumarkin (Australia/Ukraine) visited the IIML for a full-day session with our postgraduate students on 9 August 2019. Author, biologist and MA workshop member Danyl Mclauchlan took notes.

Maria Tumarkin promises not to scream too loudly. We’re in the seminar room in the Stout Research Centre and we’ve been asked not to make too much noise because it’ll disturb the scholars in the adjacent rooms. She’s standing at the front of the class, next to a whiteboard and a projector screen.

Tumarkin is an essayist and historian. She grew up in the Soviet Union, moved to Australia as a teenager before the collapse of communism; finished a Phd in cultural history; teaches writing at Melbourne University. Today she’s speaking to a crowded room of Victoria University creative writing students and affiliated poets, short-story writers, novelists and essayists, talking to us about writing at a pitch and intensity that often threatens the spirit of the no-screaming promise without ever quite breaking its word.

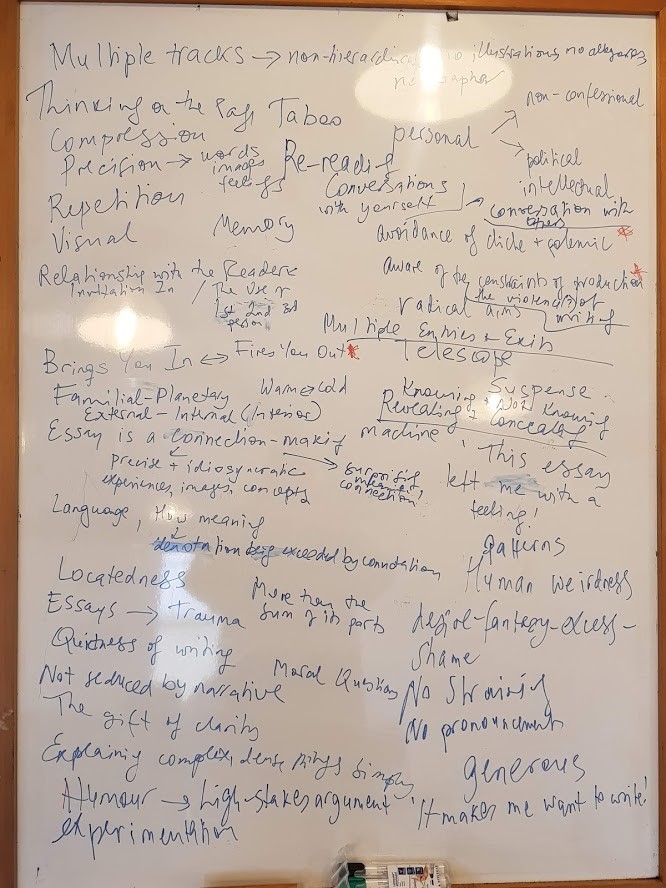

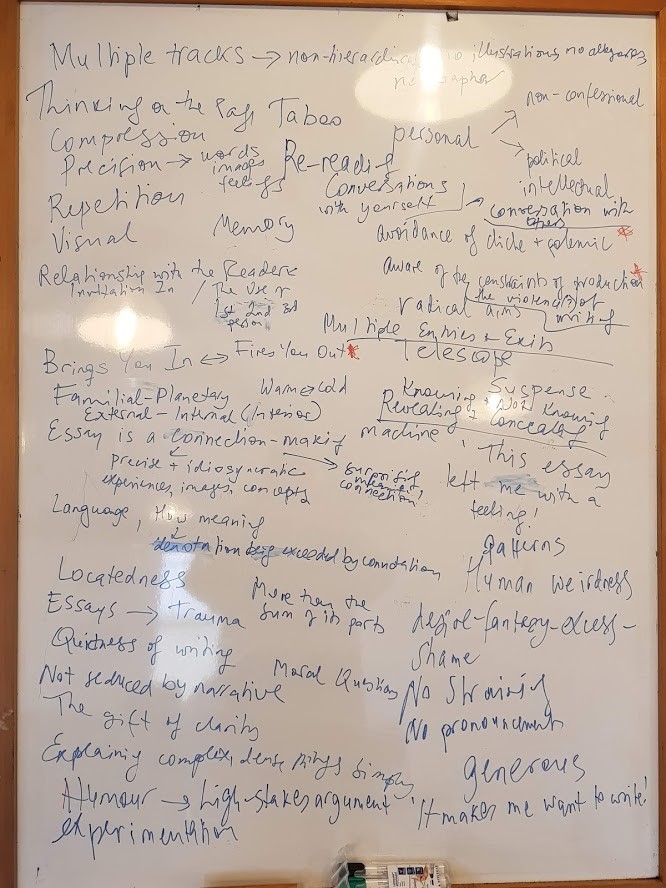

We begin with our homework. Tumarkin asked us all to provide a paragraph from an essay we love and then speak to it, although she gives us permission to ramble about anything instead of speaking to the slide. We work our way through the quotes: it’s a diverse selection, but Ashleigh Young, Huerta Mueller, Mary Ruefle and Tumarkin herself appear multiple times. She then comments on the properties of the chosen essay while annotating a whiteboard. By lunchtime the whiteboard looks like this:

Tumarkin has complicated feelings about the modern essay. We have a reading packet featuring three of her own works. The first, This narrated life, published in The Griffith Review in 2014, questions the contemporary fetishisation of storytelling. The primacy of ‘storytelling’ among the intellectual and cultural class, who celebrate ‘the power of story’ as something unambiguously miraculous is something Tumarkin is suspicious of, and the essay interrogates why. Perhaps it is because we cannot do all of our thinking through stories? Perhaps stories are too persuasive; they can manipulate us instead of leading us to the truth? Perhaps it is because the narrative structure of stories privileges certain subjects, and the logic of the narrative dicates that they should be told in certain ways? She writes:

It is hardly accidental if many of today’s more successful live storytelling events have a whiff of this. Plenty of them also wrap around themselves a cult of faux simplicity (oh, the timeless artisan feel of stories), which obscures the artifice involved in packing the entire world into a series of tellable tales.

This model of truth as a form of entertaining storytelling leaves out important ideas that cannot be reduced to simple narrative stories, Tumarkin argues. It leaves out scientists, thinkers, educators, artists and activists who cannot reduce their ideas into such a palatable form. And it is not a substitute for genuine public debate:

. . . with its bumping of heads, its pushes and pulls, its peculiar and all-important labours – defending your position, nailing your opponents, issuing rejoinders, synthesising thought, changing your mind – that are so different to the exertions of storytelling

All of this adds up to ‘narrative fetishism’, she worries: a way of shutting our ears and eyes to the truths that hurt us the most; a way of not sharing our most important experiences and truths. Storytelling is not a strong enough construction to describe what artists – novelists, essayists, performers – do; she feels that something much deeper and more meaningful happens in the essential act of communication.

~

‘The term masterclass bugs me,’ Tumarkin announces at the beginning of the day. ‘I agree with Maggie Nelson. Artistry trumps mastery.’ So instead of a class we spend the morning discussing the different essays, taking notes on Tumarkin’s pronouncements. ‘You can have radical aims,’ she tells us, speaking of an essay about ‘the end of capitalism’, but avoid polemic and clichés of thought. The essay is not propaganda. Or: ‘there’s nothing worse than elegant variation,’ as she approvingly dissects an essays use of repetitive language. Or ‘Use multiple tracks,’ on an essay that discusses both the environment and a broken relationship, ‘But don’t use tacky metaphors.’ The tracks can converge and diverge. Should we map our essays out before we write them? ‘It’s great if you can but great if you can’t.’

There’s more. ‘The essay is a machine for making connections,’ and those connections should be surprising and highly meaningful: connections that would only occur to the person writing the essay. They show the author’s mind at work. They’re about thinking on the page. Essays are written forwards, and they’re about preserving the process of arriving somewhere – if, in fact, you do arrive.’ They’re a communal space: a conversation. ‘We should be in dialog with other writers, not co-opting them. And: you need to write against the knowingness. But this is risky and ‘And anything risky can be a disaster.’

We break for lunch.

~

The second essay in the reading packet What The Essayist Spills is a review of The Unspeakable, a collection of essays by the American essayist Megham Baum. She begins with the choices Baum made about not-naming some of the characters in her essays: a fellow writer she clashed with on a literary panel; a gay writer went out to dinner with Daum during a period in which she dressed and acted like a gay woman, and wanted gay women to think she was one of them; children she’s paired with in the Big Brothers Big Sisters program, who she can’t identify for obvious ethical and legal reasons. Tumarkin finds the withholding interesting, because Daum has been identified as an essayist who is ‘personal yet anti-confessional’. Thus, perhaps, the title The Unspeakable:

Unspeaking as in walking ideas and experiences back from the ready-made language and the ready-made audience for their telling. Unspeaking as in creating a space and a distance between the lived reality and the work of writing, enabling the writer, as Deborah Levy memorably put it, ‘to chase your characters, chase your ideas’ across the page.

Tumarkin sees this is part of a broader trend in contemporary essay writing, exemplified by essayists: ‘using lived, felt experience as a starting point for her about-me-but-much-much-bigger-than-me sort of stuff.’ This category of essay:

goes about smashing the bottom from underneath the author’s experiences, thinking them out into the world, finding the language to hold them, and, crucially, steering them away from Bays of Redemption and Isles of Lessons Learned. Daum is not alone. This kind of thing – the personal essay that exceeds the contours of a singular life or mind – is its own sub-genre right now.

What Daum accomplishes, and what Tumarkin admires is the revelatory complexity of the ending of Daum’s essays. In an essay on motherhood, on the decision on whether to have children, the complexity and ambivalence of the decision and outcomes: ‘the essay’s charge comes not from identity politics, not from some stigma-busting super-moves, but from the gradually swelling recognition in a reader’s gut (if I may be so bold to speak of a reader’s gut) that we, humans, do not know what we are choosing when we end up choosing something.’ We are met with revelation, not confession.

Tumarkin – heretically – contrasts this with Roxanne Gay, who has ‘litte surprising to say’:

I understand how certain kinds of people may utter what are essentially banalities in a way so utterly disarming or credible, or carried with such a perfect mix of conviction and irony, that those banalities could be experienced by large groups of people as joyful truths. I understand that individuals possessed of such gifts are interesting precisely – if not only – because of this ability, and that they are originals in their own right. It may be that the personal essay is a special form that elevates these kinds of voices and creates these reading highs. Which is fine, and could be great, especially if this coming together through mutual recognition, the ecstatic and the communal, happens for people who usually feel on the outer of public life.

Validating the pre-existing values of the cultural class is not what essays are for, Tumarkin believes. They’re for ‘thinking about things that need to be thought about yet don’t get thought about much, or at all, or interestingly, or for long enough.’ She ends by telling us to buy Daum’s book and read Tumarkin’s favourite essay in the collection ‘Matricide’, an essay Tumarkin refuses to tell the reader anything about (There’s an abridged version of this essay at the Guardian website, if you want to follow her advice).

~

After lunch we work through Tumarkin’s slide show, beginning with quotes that also featured in Tumarkin’s Daum review:

‘All the best essays are epistemological journeys from ignorance or curiosity to knowledge.’ – Geoff Dyer

‘The essay’s job is to track consciousness … Instead of lecturing you, [the essay] invites you into the pathways of the mind of a writer who’s examining, testing, and speculating.’ – Philip Lopate

‘The truth to which the essay has access emerges only at the point where thinking, in an effort to remedy the insufficiency of existing categories, drives thought beyond its own boundaries…’ – Adorno.

Here is Tumarkin’s Anatomy of an Essay, a representation of one of her writing processes:

OBSERVATION

↓

IRRITATION

↓

QUESTION

↓

VIABILITY TEST

↓

RESEARCH

↓

WRITING

And here’s how this works. ‘I’ll notice something like: all the shops in my neighbourhood kept closing down and being replaced by cafes and other places that sell food,’ Tumarkin explains. ‘And it irritated me that I kept thinking about that. So I ask myself: is there an essay there. Can I write something interesting? Has anyone else noticed this and written about it? And then I research. And I love to research. I’d be happy doing the research forever and ever and none of the writing. But you have to write.’

A quote from Zadie Smith on the slide show:

When I write I am trying to express my way of being in the world. This is primarily a process of elimination: once you have removed all the dead language, the second-hand dogma, the truths that are not your own but other people’s, the mottos, the slogans, the out-and-out lies of your nation, the myths of your historical moment – once you have removed all that warps experience into a shape you do not recognise and do not believe in – what you are left with is something approximating the truth of your own conception.’

And the slide show ends with Tumarkin’s list of vital contemporary essayists:

Zadie Smith, Helen Garner, Joan Didion, Virginia Woolf, Anne Carson, Eliot Weinberger, David Foster Wallace, Annie Dillard, Roland Barthes, Jenny Diski, Maggie Nelson, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Leslie Jamison, Christopher Hitchens, Teju Cole, Patricia Lockwood, Ashleigh Young, Sarah Manguso, Fiona Wright, Meghan Daum, Mary Ruefle, Rebecca Solnit, Geoff Dyer, Brian Dillon, Alexander Chee, Wesley Morris, John Jeremiah Sullivan, Anne Boyer, Robert Dessaix, Durga Chew-Bose, Sinead Gleeson, Kate Briggs, Alexander Hemon, Ariel Levy, Valeria Luiselli, Marilynne Robinson

~

The final work in the reading packet is you can’t enter the same river twice from her new collection Axiomatic, a work in which she puts most of her ideas about the contemporary essay into practise. The essay consists of two voices: Tumarkin’s and her closest childhood friend, who she was inseparable from growing up. They’re speaking of their lives back in the Soviet Union, the times when when they were teenagers, their friendship over time; history; memory. Life. The voices appear in columns, side-by-side, unless they don’t: sometimes a single voice takes over the width of the page. They repeat themselves, loop back, interrogate the validity of their memories. They talk to each other; contradict each other. They quote diaries, poems, letters. Dreams. The voices seem to merge and part. It’s fascinating seeing the author’s ideas cohere into a creative work, but it’s also very hard to quote from representatively (this too is possibly not accidental).

~

The final session of the day is on the perennial issue of ethics in writing non-fiction.

‘Some things are black and white in the ethics of non fiction writing,’ Tumarkin warns us. ‘If you’re fabricating anything you’re writing fiction. If you’re intentionally misleading your readers via framing or important omissions you’re writing fiction. If you’re creating characters or inventing composite characters you’re writing fiction. If you’re making up quotes, misattributing quotes, putting yourself into the middle of a story when you weren’t there, changing the timeline to intensify the drama or ‘interviewing the dead’ (‘The dead are not up for grabs,’ Tumarkin insists) then you’re writing fiction and you need to alert the reader to

this.’ ‘If you don’t remember something, admit this instead of covering it up. Many powerful memoirs have ‘darkness at the centre of the map’. When you leave nonfiction behind and start writing fiction you buy yourself a real freedom,’ she concludes. ‘But you leave behind the power of the real.’

She quotes the American journalist John Hersey:

‘Subjectivity and selectivity are necessary and inevitable in non-fiction. If you gather 10 facts but wind up using nine, subjectivity sets in. This process of subtraction can lead to distortion. Context can drop out, or history, or nuance, or qualification or alternative perspectives. While subtraction may distort the reality you are trying to represent, the result is still nonfiction. The addition of invented material, however, changes the nature of the beast. When we add a scene that did not occur or a quote that was never uttered, we cross the line into fiction. If you’re in a gray area around any of these issues you’re writing fiction.’

Someone asks: ‘What about remembering painful things?’ ‘Writing is not therapy,’ Tumarkin replies. ‘You don’t necessarily have to write what shames you. You don’t have to go into the dark recesses of your soul.’

Not only do we have ethical obligations to our readers, she warns us, we have ethical obligations to our subjects: ‘Do not leave someone else’s world diminished, poorer than it

was before your entry into it.’ You should have consent from your subjects, but consent is only the beginning. Don’t treat your subjects as characters. They’re real people. Grant them complexity. And consent is no antidote to exploitation, appropriation and exoticism. Ask yourself: what are you taking and what are you giving back?’

And you should revisit these issues of consent. Most people have not considered what it will be like to be written about. You need to inform them. You should offer them anonymity. ‘Put yourself through the ethical mincer.’

Someone in the class asks ‘What’s the best way to write about family in an ethical way?’

‘Make way for tension, disagreements and other versions,’ she advises. Her arrangement with her own mother is a negotiated deal that her mother can take things out.

Next we walk through a couple of ethical case studies. (We’re rushed for time and skip past a series of slides on Karl Ove Knausgard and some in the room cheer quietly.)

~

In 2004 Ann Patchett published Truth and Beauty, an autobiographical account of her friendship with the poet Lucy Grealy. Grealy had jaw cancer as a child; the removal of the tumour left her with facial disfigurement; many reconstructive surgeries left her with an addiction to painkillers. She died of a heroin overdose at the age of 39. Patchett had consent from Grealy’s family to quote from her letters, but it was a consent they bitterly regretted once the book was published and they saw that it depicted Grealy as brilliant but deeply flawed, self-absorbed, even parasitic. Grealy’s sister attacked Patchett in the media as a ‘grief thief’.

‘Patchett has every right to tell the story of her friendship and her loss, but there are other issues here.’ Tumarkin argues. Lucy Grealy can’t speak back to Patchett’s book: we must consider the human rights of the dead.’ Is Patchett turning Grealy into a commodity? Are there issues of the abled exploiting the disabled? On the other hand: isn’t Patchett honouring Grealy by depicting her complexity? Isn’t she helping to keep her memory alive?

Second case study: Boy, Lost, by the Australian writer Kristina Olsson is a reconstruction of Olsson’s mother’s early life, written after her mother’s death, about parts of her life she never discussed with her children. Olsson’s solution is to let the reader know that the book is based on rigorous research but also ‘an act of imagining’. She acknowledges the gaps and silences in the material:

‘This is the story my mother never told, not to us, the children who would grow up around it in the way that skin grows over a scratch. So we conjured it, guessed it from glances, from echoes, from phrases that snap in the air like a bird’s wing, and are gone.’

~

The last few moments of the class are about form. you can’t enter the same river twice uses experimental form but Tumarkin warns us not to use ‘complexity and fragmentation as an excuse to cover up writerly laziness and bad thinking.’ You have to do the hard work, she warns. ‘You have to go through the dark forest, like Dante did, and then your writing will be good work instead of shit lazy work. Any more questions?’

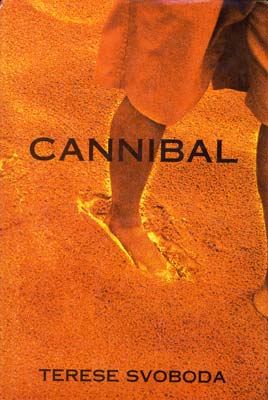

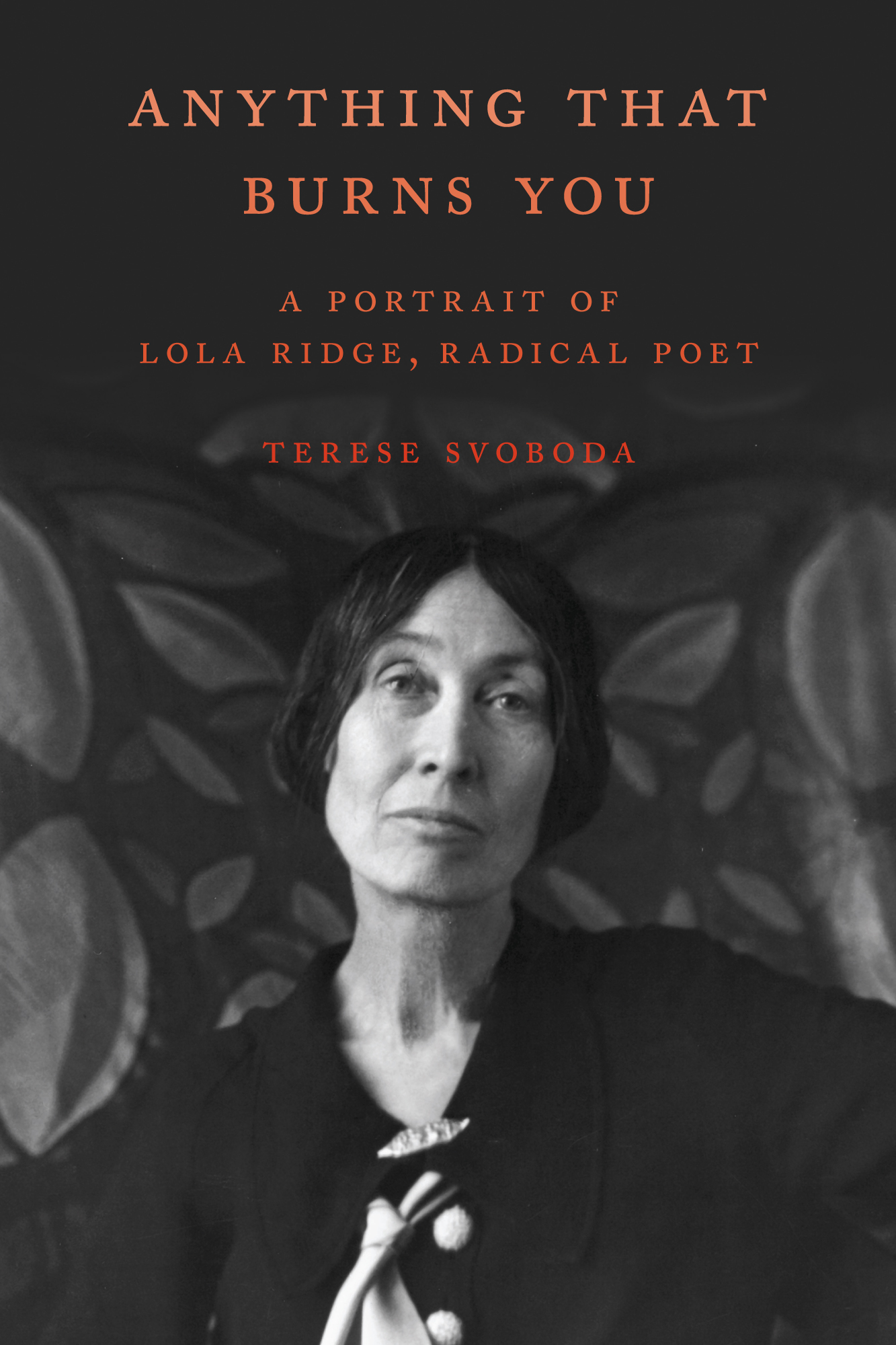

On 16 May, the MA students were honoured to attend a full day masterclass with Terese Svoboda, the author of six novels, a short fiction collection due out next year, seven poetry collections, a book of translation, a biography and a memoir. Her novel Cannibal was named one of ten best westerns of the year and described by one reviewer as ‘a female Heart of Darkness’. Her video work is also award-winning and she’s received a Guggenheim.

On 16 May, the MA students were honoured to attend a full day masterclass with Terese Svoboda, the author of six novels, a short fiction collection due out next year, seven poetry collections, a book of translation, a biography and a memoir. Her novel Cannibal was named one of ten best westerns of the year and described by one reviewer as ‘a female Heart of Darkness’. Her video work is also award-winning and she’s received a Guggenheim. made her want to write fiction. This became Cannibal, her first novel. It was fifteen years in the making, during which time she grappled with some of the differences between poetry and fiction. Poetry occurs in a single moment on a white page, whereas fiction, she was told, emphasised character development and plot, and she was always bored with how to open and close doors in the prose. She says if she weren’t always ‘rebelling against these things’, she would have learned earlier that ‘story is a magical thing that you unearth and discover’ – but magic takes work.

made her want to write fiction. This became Cannibal, her first novel. It was fifteen years in the making, during which time she grappled with some of the differences between poetry and fiction. Poetry occurs in a single moment on a white page, whereas fiction, she was told, emphasised character development and plot, and she was always bored with how to open and close doors in the prose. She says if she weren’t always ‘rebelling against these things’, she would have learned earlier that ‘story is a magical thing that you unearth and discover’ – but magic takes work. A turning point in Terese’s writing life was attending Gordon Lish’s famed writing workshops. She describes these in riveting detail. Lish looked ‘like a Presbyterian minister’, she says, ‘but kind of evil, like Sam Peckinpah’. You weren’t allowed to pee at any point during the sessions, even Terese, who was pregnant at the time. Not only that but the sessions were very long: it wasn’t unusual to finish up at 2am. People would break down, there would be people next to her on respirators, people with two weeks left to live. He made you believe fiction was worth devoting your life to. It was like EST or brainwashing, you emerged believing that.

A turning point in Terese’s writing life was attending Gordon Lish’s famed writing workshops. She describes these in riveting detail. Lish looked ‘like a Presbyterian minister’, she says, ‘but kind of evil, like Sam Peckinpah’. You weren’t allowed to pee at any point during the sessions, even Terese, who was pregnant at the time. Not only that but the sessions were very long: it wasn’t unusual to finish up at 2am. People would break down, there would be people next to her on respirators, people with two weeks left to live. He made you believe fiction was worth devoting your life to. It was like EST or brainwashing, you emerged believing that. Terese wrote a biography of Lola Ridge, an anarchist Modernist poet and committed activist. Her second book was from the point of view of a little Australiasian bad girl. She was born in Dublin and emigrated to New Zealand as a child and spent 23 years here before emigrating to New York City, where she received very favourable critical attention as a writer and was an editor at avant garde literary journals. She had a personal relationship with all the big names in New York at that time (between the wars): Marianne Moore was one of her best friends. At her death, the New York Times declared her “one of America’s most important poets.” Despite this, she’s been largely forgotten in New Zealand and the United States. Why is that? Part of it has to do with the politics of the canonisers, Terese argues. Influential Elliot and Pound were elitist, whereas Ridge was vocally and uncompromisingly for the radical left. Women poets were also perceived as a threat during the time Ridge was active, following the immense publishing success of Edna St Vincent Millay. As a result, women poets were widely denigrated. She was also experimental at a time when poets looked for form. Others have seen her perspective with regard to her radical interests in those who were lynching or executed as ‘maternal’, but Terese argues that Ridge always writes from a female point of view and that’s so rare it’s seen as maternal.

Terese wrote a biography of Lola Ridge, an anarchist Modernist poet and committed activist. Her second book was from the point of view of a little Australiasian bad girl. She was born in Dublin and emigrated to New Zealand as a child and spent 23 years here before emigrating to New York City, where she received very favourable critical attention as a writer and was an editor at avant garde literary journals. She had a personal relationship with all the big names in New York at that time (between the wars): Marianne Moore was one of her best friends. At her death, the New York Times declared her “one of America’s most important poets.” Despite this, she’s been largely forgotten in New Zealand and the United States. Why is that? Part of it has to do with the politics of the canonisers, Terese argues. Influential Elliot and Pound were elitist, whereas Ridge was vocally and uncompromisingly for the radical left. Women poets were also perceived as a threat during the time Ridge was active, following the immense publishing success of Edna St Vincent Millay. As a result, women poets were widely denigrated. She was also experimental at a time when poets looked for form. Others have seen her perspective with regard to her radical interests in those who were lynching or executed as ‘maternal’, but Terese argues that Ridge always writes from a female point of view and that’s so rare it’s seen as maternal.